- About Us

- Events & Training

- Professional Development

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- Resources

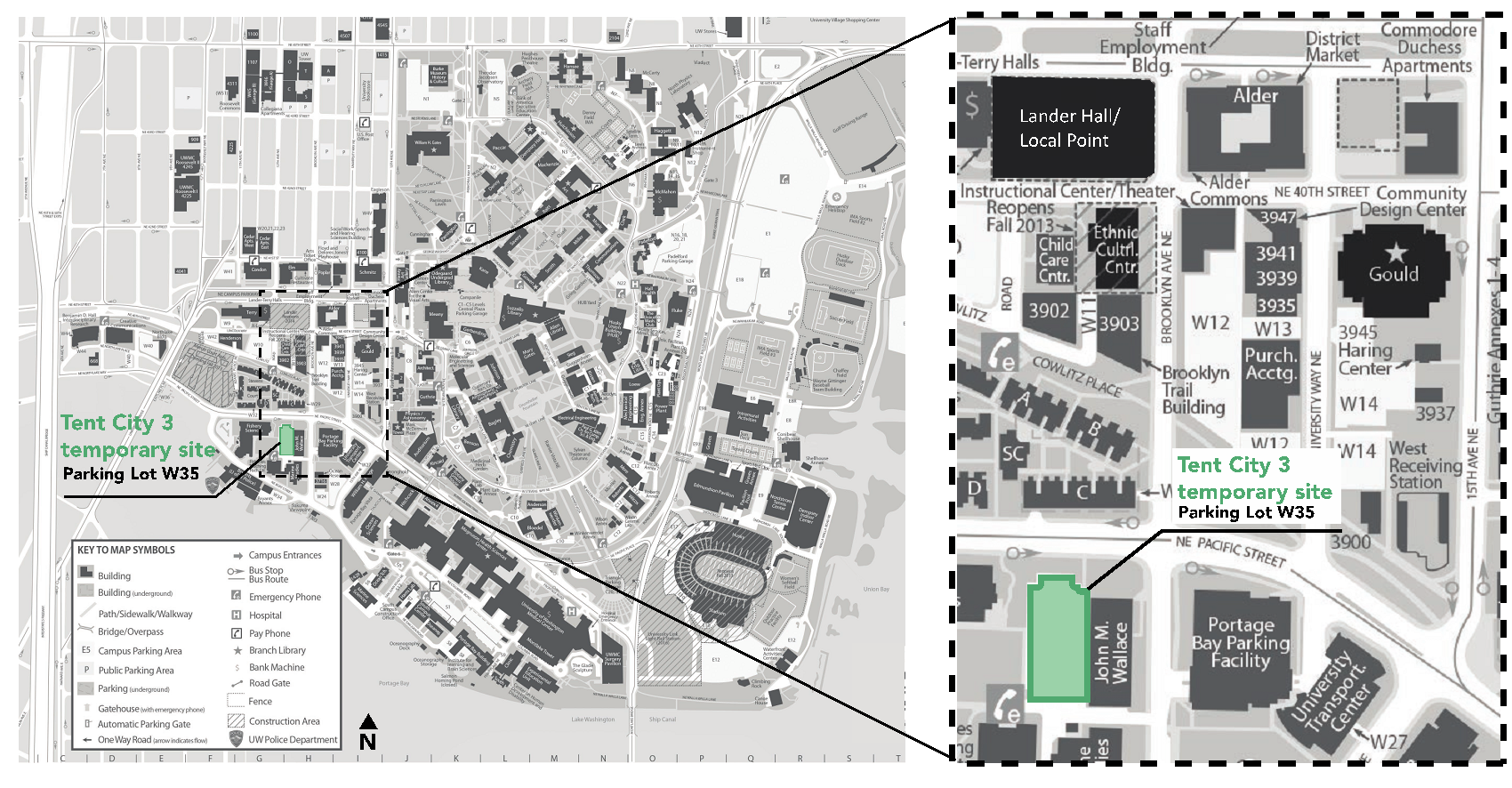

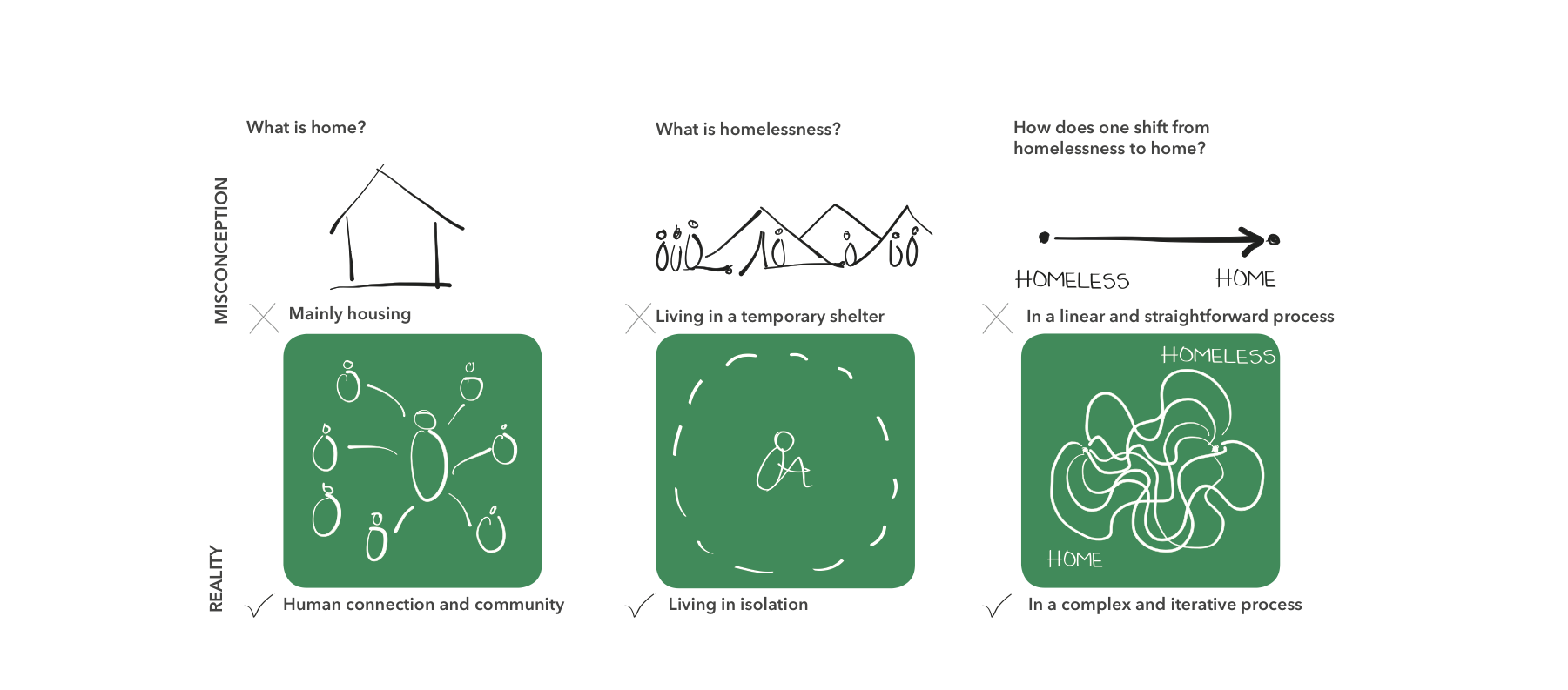

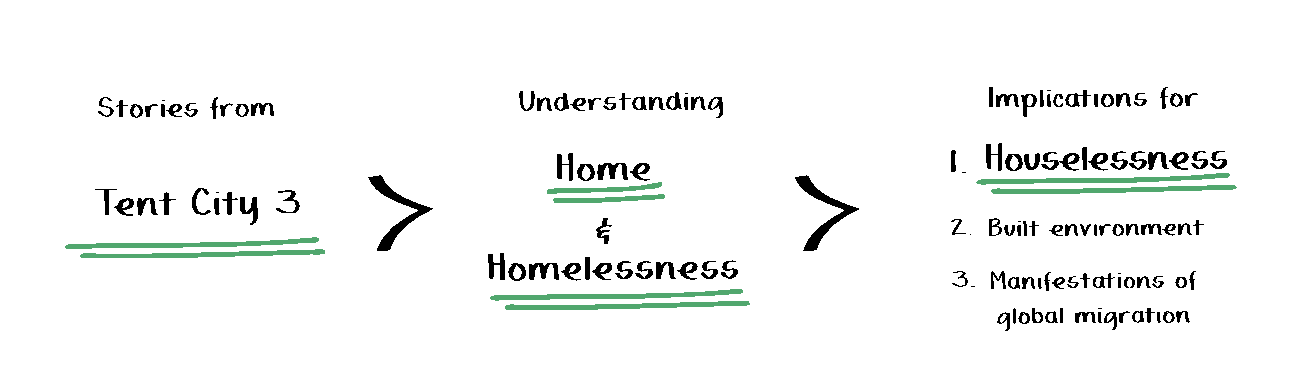

Rethinking “Home” Through the Lens of “Homelessness” and Why This Is Relevant to Urban Planning and Public PolicyBy Ru’a Al-Abweh A recent UW graduate presents her scholarship-winning research on homelessness and the perception of “home.” Of the numerous vocabularies in the English language, “home” is perhaps one of the most complex and contested. Everyone may have a different understanding of what constitutes a home, but most will likely agree that it is not synonymous to “house” but is instead combination of various factors: family, friends, shelter, safety, belonging, community, privacy, a sense of self, a sense of ease, and more. So while there is general consensus that “home” is not simply a “house,” why is the lack of housing—more often than not, in and of itself—labeled as “homelessness?” For my Master of Urban Planning thesis at the University of Washington, I decided to question, challenge, and test current meanings of home and homelessness. In an attempt to better understand the critical case of houselessness in Seattle and elsewhere in the U.S., I decided to delve deep into understanding what “home” means to people that society often sees as “homeless.” With a particular interest in communal living, I collected perspectives on “home” from Tent City 3, a self-governed encampment that changes location every three months and was hosted on the University of Washington campus from December 17, 2016 to March 18, 2017.

The main question I wanted to answer through stories from Tent City 3 was, “What does home mean for those who are “unsettled,” occupying spaces not considered rightfully theirs, and perceived as “the other?” The members of Tent City 3 shared various stories about how and why they lost housing and joined Tent City 3, in addition to the often-changing meaning of home throughout their lives. Despite the differences, there were also many commonalities found in the stories of “home”—the most important of which being the centrality of human connection and community. Many told stories of troubled family relationships or difficult fallouts with friends, which were frequently the main drivers in causing people to lose a sense of home—and consequently, eventually lose housing. Some even said that they only regained a sense of home—or found it for the first time ever—upon joining Tent City 3.

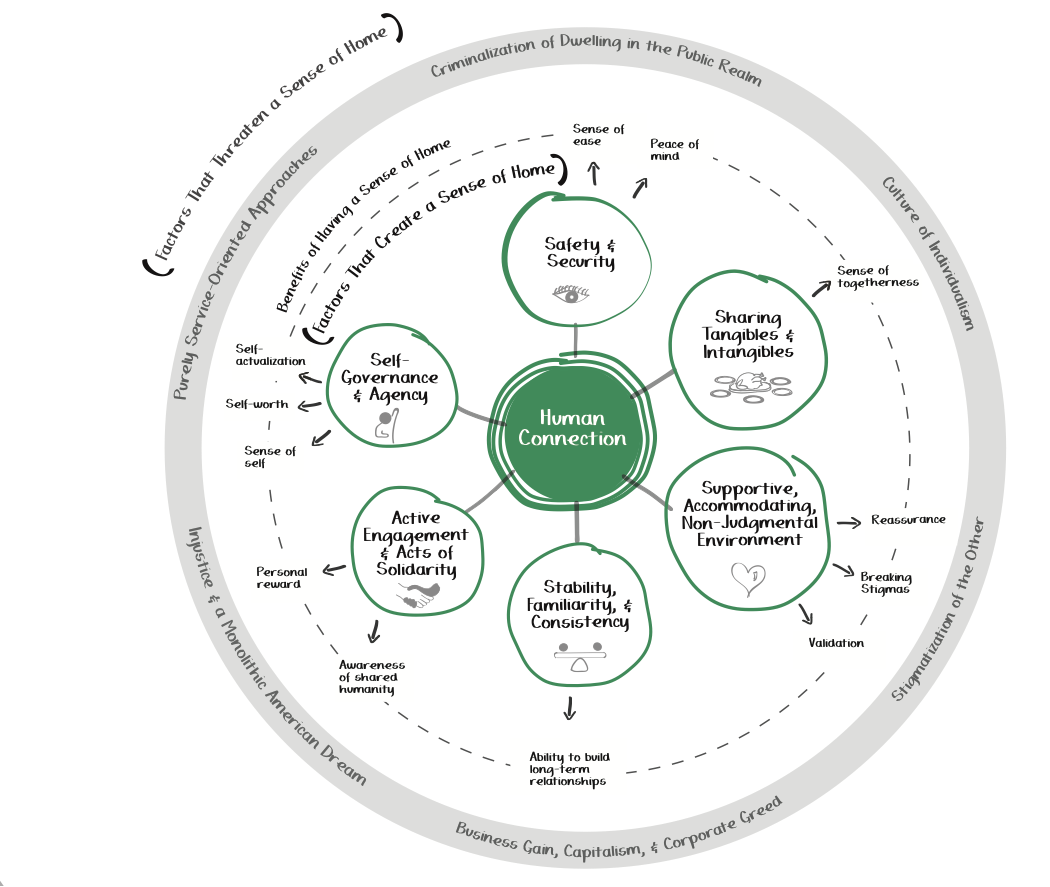

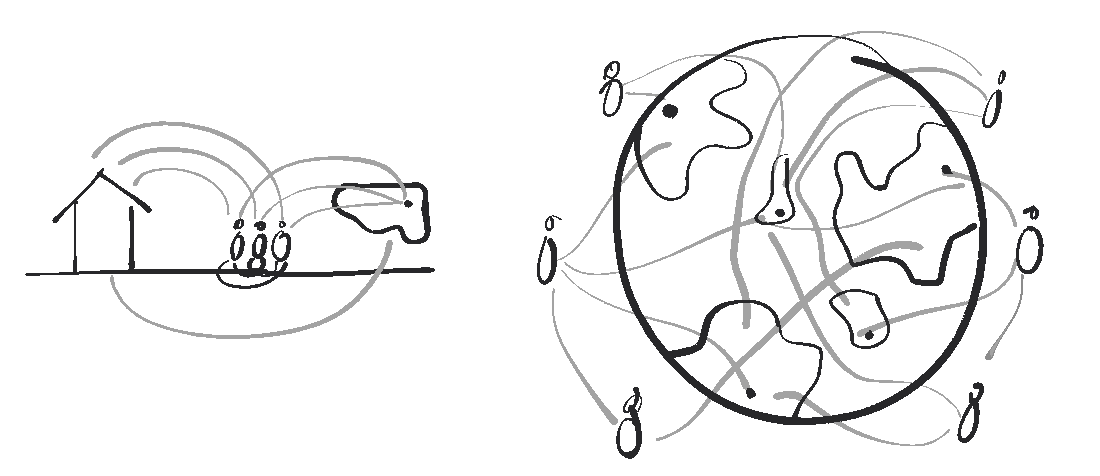

Through the invaluable personal stories from Tent City 3, I created the “Home Framework,” a conceptual framework that summarizes the common story themes under two main questions: What Creates a Sense of Home and External Factors That Threaten a Sense of Home. Each of these two questions has a series of associated facets, in addition to explaining the Benefits of Having a Sense of Home.

While the main implications of this research are a reconsideration of the approaches to houselessness used in urban planning and public policy there are also important implications for the planning and design of the built in environment in general and for manifestations of global migration.

Reframing home and homelessness has the potential to create a shift in the established values and cultural constructs in planning and public policy, which often make too direct a correlation between permanent housing and “home.” At a time in which houselessness is a chronic emergency for far too many and global migration is on the rise, this is a key moment to remember that “home” often surpasses a single place, person, or situation. Furthermore, calling into question the role of planning and public policy in helping to cultivate a sense of home is equally as important. With the understanding that a sense of community is at the core of “home”, planning and public policy can emphasize the development of socially resilient cities where people of all different circumstances can feel accommodated, welcome, and at home –regardless of their housing situation.

To view and download the complete thesis, What Makes People Feel at Home? Reframing Home and Homelessness Through Stories from Seattle’s Tent City 3, follow the link. Return to the September/October issue of The Washington Planner |